This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning. Explore all of our newsletters here

Welcome back. It’s well known that Poland has been among the staunchest supporters of Ukraine since the full-scale Russian invasion of February 2022. It’s also well known that Poland’s coalition government, under Prime Minister Donald Tusk, takes a much more constructive approach to the EU than did its rightwing nationalist predecessor.

So why did a senior Polish government minister say this week that Ukraine should not be allowed, under present circumstances, to join the EU? I’m at [email protected].

Unhealed wounds of the 20th century

The official in question was Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, who serves as deputy premier and defence minister in Tusk’s government. Speaking to the broadcaster Polsat on Wednesday, he said Poland would block Ukraine’s EU membership bid as long as the authorities in Kyiv continue to play down the Volhynia massacres of ethnic Poles by Ukrainian ultranationalists during the second world war.

I wish to make two points about the minister’s comments. The first is that they illustrate how disputed interpretations of history are a more serious obstacle to the EU’s proposed enlargement into eastern and south-eastern Europe than is often understood.

Recently, this problem has come to the fore in relations between Bulgaria, an EU member state, and North Macedonia, which aspires to join the club — as I set out in this newsletter in April.

People hold flags and banners during a march, commemorating the ethnic Poles massacred by Ukrainian ultranationalists in Volhynia and eastern Galicia during the second world war, in Krakow on July 10 2022 © Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The massacres in Volhynia and eastern Galicia in 1943-1945 rank among the darkest episodes in Polish-Ukrainian history. Each side perpetrated atrocities against civilians (as Ukrainian news outlets are quick to point out), but not in equal measure.

You will find a lucid and fair-minded assessment of what happened, and how the burden of the past weighs heavily on the present, in this essay by Alex Perez-Reyes for the Washington-based Wilson Center.

Allies in a common cause

My second point is that the Tusk government’s disapproval of Ukraine’s attitude to the Volhynia massacres echoes that of Poland’s former government, led by the conservative nationalist Law and Justice (PiS) party, which lost power after October’s parliamentary elections.

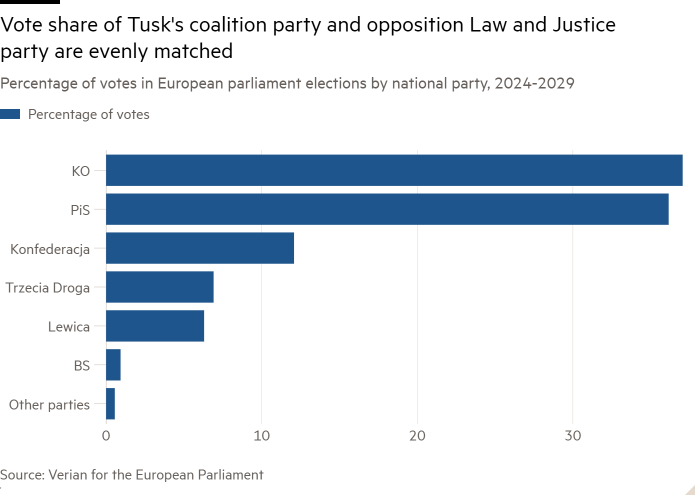

Poland is a country sharply polarised between its two major political forces, Tusk’s Civic Platform and PiS. The results of last month’s European parliament elections confirmed this trend, as the chart below shows.

But in the controversy over the Volhynia massacres, the two parties are broadly on the same side of the argument.

In 2016, when PiS was in power, Poland’s parliament passed a resolution that labelled the massacres “genocide”. Some 432 legislators in the 460-seat assembly voted in favour.

Meanwhile, the Tusk government has followed its predecessor — though less stridently — by displaying sympathy for Polish farmers demanding restrictions on imports of agricultural products from Ukraine. This is another issue that obstructs Ukraine’s path towards the EU.

Perhaps, as Edwin Bendyk argues for the European Council on Foreign Relations, the agricultural dispute is “not of strategic importance”. It is certainly true that in most respects Polish support for Ukraine remains strong.

The two countries are allies in a common cause. In early July, Tusk and Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed a security co-operation pact.

For Poles as much as for Ukrainians, the overriding threat comes from Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Nevertheless, historical memory and the agricultural problem are two thorns in Polish-Ukrainian relations.

The German question

History also casts shadows over the relationship between Poland and Germany. Tensions between the two countries rose during the 2015-2023 rule of PiS to their highest level since Poland threw off communism in 1989.

One reason was the PiS-led government’s demand for €1.3tn in reparations for the depredations that Poland suffered at the hands of Nazi invaders in the second world war.

The government was also severely critical of Germany’s insistence on maintaining close economic ties with Russia, a policy exemplified by the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project. Just weeks before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Mateusz Morawiecki, then the Polish prime minister, accused Germany of “loading Putin’s pistol, which he can then use to blackmail the whole of Europe”.

After the invasion, Germany quickly dropped the pipeline project. Now the Tusk government is working hard to put ties between Warsaw and Berlin on a more positive footing — without, however, abandoning financial claims related to the Nazi occupation of Poland.

At the start of July, the two countries held their first intergovernmental consultations since 2018 and made some progress on defence and security issues. However, as Łukasz Jasiński wrote for the Polish Institute of International Affairs:

There has been no significant progress on the issue of compensation and support for the Polish victims of the German occupation.

Weimar Triangle, Visegrád Group and the UK

Nato and the EU are the anchors of Poland’s security, but most governments in Warsaw since 1989 have tried to supplement them with regional co-operation initiatives. The most prominent are the Weimar Triangle, linking France, Germany and Poland, and the Visegrád Group, uniting the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia.

For reasons that are partly beyond Poland’s control, these associations have delivered modest results at best.

Under the PiS-led government, the Weimar Triangle fell into disuse, as Philipp Fritz explains in this article for Visegrad Insight. Under Tusk, Poland has tried to revive it, and the three governments claimed some success earlier this year when they presented a united front in Washington to argue for a resumption of US military and financial aid for Ukraine.

However, the recent French parliamentary elections have cast doubt over the coherence and long-term direction of Paris’s foreign policy, leaving President Emmanuel Macron weakened and no political party with a legislative majority. This is likely to undermine the usefulness of the Weimar Triangle, which holds little interest for the French radical left and right.

As for the Visegrád Four, the return to power of Robert Fico in Slovakia has turned a loosely organised group that was already in trouble, thanks to the foreign policy antics of Hungarian premier Viktor Orbán, into a diplomatic irrelevance.

On foreign policy issues, above all support for Ukraine, as well as on domestic matters such as the rule of law, Hungary and Slovakia are nowadays far apart from the Czech Republic and Poland.

Robert Beck, a distinguished US expert on the region, describes the Visegrád group as “in tatters with no short-term prospects for meaningful co-operation”.

A third component of Poland’s European policies is the relationship with the UK. Here the picture is mixed but by no means bleak.

Polish policymakers were aghast at Brexit, since London was often an important ally at the EU table. However, the two countries remain close on defence, security and intelligence matters and see eye to eye on support for Ukraine.

Trump 2.0: not such a worry for Poland?

For many Poles, the nation’s most vital international ally is the US. Like its European partners, the Tusk government sees an urgent need to prepare for Donald Trump’s possible return to the White House after November’s presidential election.

However, we should keep in mind that, in contrast to some European countries, notably Germany, Poland had a flourishing relationship with the US during Trump’s first term.

Bastian Sendhardt, writing for the International Politics and Society journal in August 2020, put it well:

Because the Trump administration sees Poland as an anchor in a deeply Trump-critical Europe, the Polish government is attempting to use multiple disagreements between the US president and countless European governments — including Germany — for its own advantage. Poland therefore considers itself as an arbiter between the US on the one hand, and the EU and its member states on the other.

The all-important question is whether the warm ties of Trump’s first term could be replicated in a second term, given that PiS — a party that positioned itself close to Trumpian Republicanism — has been supplanted by a government that is distinctly more liberal-minded and pro-EU.

Radek Sikorski, Poland’s foreign minister, sees the problem. Earlier this month, he circulated among his EU counterparts a discussion paper that contended Europeans must do a better job of explaining the value of the transatlantic alliance to US policymakers and opinion-formers.

National unity

At times over the past 10 years, quarrels over foreign policy — relations with the EU, attitudes to Germany and more — have inflamed the bitter domestic disputes that divide Poland’s main political parties.

This trend has persisted despite the general consensus on the need to support Ukraine and stand firm against Russia.

The security threats facing Poland, and Europe as a whole, suggest that the political parties would be wise not to let their arguments with each other undermine national unity.

Poland could be Europe’s rising star on defence and security — a commentary by Armida van Rij and Melania Parzonka for the London-based Chatham House think-tank

Tony’s picks of the week

Fears that our children will inherit a world of terrible inequality, collapsing public services, high debt and a damaged planet are yielding to hopes that the economies of advanced countries can break decisively out of a low-growth rut, economist and investor Mohamed El-Erian writes for the FT

Russia’s use of the Caspian Sea for military purposes and its reduction of water flow from the Volga are damaging the sea’s already fragile ecosystem, Zaur Shiriyev contends in a commentary for Carnegie Politika

Recommended newsletters for you

The State of Britain — Helping you navigate the twists and turns of Britain’s post-Brexit relationship with Europe and beyond. Sign up here

Working it — Discover the big ideas shaping today’s workplaces with a weekly newsletter from work & careers editor Isabel Berwick. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe

Source link : https://www.ft.com/content/05590f03-bce6-4632-9968-eb1f3ffb96a3

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-27 10:00:51

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.

Author : love-europe

Publish date : 2024-07-27 11:18:11

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.